Who Owned And Controlled The Soviet Union's Collective Farms

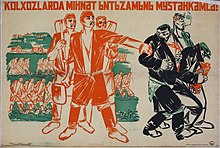

Illustration to the Soviet categories of peasants: bednyaks, or poor peasants; serednyaks, or mid-income peasants; and kulaks, the college-income farmers who had larger farms than almost Russian peasants. Published in Projector, May 1926.

The Soviet Marriage introduced the collectivization (Russian: Коллективизация) of its agricultural sector between 1928 and 1940 during the ascension of Joseph Stalin. It began during and was part of the first five-year programme. The policy aimed to integrate individual landholdings and labour into collectively-controlled and state-controlled farms: Kolkhozes and Sovkhozes accordingly. The Soviet leadership confidently expected that the replacement of individual peasant farms past collective ones would immediately increase the food supply for the urban population, the supply of raw materials for the processing industry, and agricultural exports via country-imposed quotas on individuals working on collective farms. Planners regarded collectivization as the solution to the crunch of agricultural distribution (mainly in grain deliveries) that had developed from 1927.[one] This problem became more than acute equally the Soviet Union pressed ahead with its aggressive industrialization program, meaning that more food needed to exist produced to keep upwards with urban need.[2]

In the early 1930s, over 91% of agronomical land became collectivized as rural households entered collective farms with their land, livestock, and other assets. The collectivization era saw several famines, many due to both the shortage of mod engineering science in USSR at the fourth dimension. The death cost cited past experts has ranged from iv million to 7 million.[3]

Background [edit]

After the emancipation of the serfs in 1861, peasants gained control of almost one-half of the land they had previously cultivated and began to inquire for the redistribution of all land.[4] The Stolypin agricultural reforms between 1905 and 1914 gave incentives for the creation of big farms, but these concluded during Globe War I. The Russian Conditional Government achieved little during the difficult World War I months, though Russian leaders connected to hope redistribution. Peasants began to turn against the Provisional Government and organized themselves into land committees, which together with the traditional peasant communes became a powerful strength of opposition. When Vladimir Lenin returned to Russia on April xvi, 1917, he promised the people "Peace, State and Bread," the latter two appearing as a promise to the peasants for the redistribution of confiscated state and a fair share of food for every worker respectively.

During the period of war communism, nonetheless, the policy of Prodrazvyorstka meant that the peasantry was obligated to give up the surpluses of agricultural produce for a fixed price. When the Russian Civil War ended, the economy changed with the New Economic Policy (NEP) and specifically, the policy of prodnalog or "food tax." This new policy was designed to re-build morale among embittered farmers and lead to increased product.

The pre-existing communes, which periodically redistributed state, did lilliputian to encourage improvement in technique and formed a source of power beyond the control of the Soviet regime. Although the income gap between wealthy and poor farmers did grow nether the NEP, information technology remained quite small, simply the Bolsheviks began to accept aim at the kulaks, peasants with plenty land and coin to own several animals and hire a few labourers. Kulaks were blamed for withholding surpluses of agricultural produce. Clearly identifying this group was difficult, though, since only most 1% of the peasantry employed labourers (the basic Marxist definition of a backer), and 82% of the country's population were peasants.[four] According to Robert Conquest, the definition of "kulak" also varied depending on who was using it; "peasants with a couple of cows or v or six acres [~ii ha] more than than their neighbors" were labeled kulaks" in Stalin'due south outset Five Year Plan.[5]

The small shares of nearly of the peasants resulted in food shortages in the cities. Although grain had most returned to pre-war production levels, the large estates which had produced information technology for urban markets had been divided up.[4] Not interested in acquiring money to purchase overpriced manufactured goods, the peasants chose to consume their produce rather than sell it. As a result, city dwellers just saw half the grain that had been available before the state of war.[4] Before the revolution, peasants controlled simply ii,100,000 km² divided into xvi 1000000 holdings, producing l% of the nutrient grown in Russia and consuming 60% of full food production. Later the revolution, the peasants controlled 3,140,000 km² divided into 25 million holdings, producing 85% of the food, simply consuming 80% of what they grew (meaning that they ate 68% of the total).[6]

The Communist Party of the Soviet Union had never been happy with private agriculture and saw collectivization equally the best remedy for the problem. Lenin claimed, "Small production gives nativity to capitalism and the suburbia constantly, daily, hourly, with elemental force, and in vast proportions."[7] Autonomously from ideological goals, Joseph Stalin as well wished to embark on a plan of rapid heavy industrialization which required larger surpluses to be extracted from the agricultural sector in society to feed a growing industrial workforce and to pay for imports of machinery (by exporting grain).[8] Social and ideological goals would as well be served through the mobilization of the peasants in a co-operative economic enterprise that would provide social services to the people and empower the land. Not only was collectivization meant to fund industrialization, but it was besides a way for the Bolsheviks to systematically exterminate the Kulaks and peasants in full general in a back-handed manner. Stalin was incredibly suspicious of the peasants, viewing them as a major threat to socialism. Stalin's use of the collectivization process served to not just address the grain shortages, but his greater concern over the peasants' willingness to conform to the collective farm system and state mandated grain acquisitions.[9] He viewed this as an opportunity to punish the Kulaks as a form by ways of collectivization.

Crisis of 1928 [edit]

This need for more than grain resulted in the reintroduction of requisitioning which was resisted in rural areas. In 1928 in that location was a two-million-ton shortfall in grains purchased by the Soviet Union from neighbouring markets. Stalin claimed the grain had been produced but was beingness hoarded by "kulaks." Stalin tried to appear equally being on the side of the peasants, but it did not assist, and the peasants as a whole resented the grain seizures. The peasants did everything they could to protest what they considered unfair seizures.[9] Instead of raising the price, the Politburo adopted an emergency measure to requisition ii.5 million tons of grain.

The seizures of grain discouraged the peasants and less grain was produced during 1928, and over again the authorities resorted to requisitions, much of the grain existence requisitioned from middle peasants as sufficient quantities were not in the hands of the "kulaks." The impact that this had on poorer peasants forced them to move to the cities. The peasants moved in search of jobs in the quickly expanding industry. This, notwithstanding, had a fairly negative impact upon their inflow equally the peasants brought with them their habits from the farms. They struggled with punctuality and demonstrated a rather poor piece of work ethic, which hindered their ability to perform in the workplace.[ten] In 1929, especially subsequently the introduction of the Ural-Siberian Method of grain procurement, resistance to grain seizures became widespread with some violent incidents of resistance. Likewise, massive hoarding (burial was the mutual method) and illegal transfers of grain took place.[ citation needed ] [xi]

Faced with the refusal to manus grain over, a determination was fabricated at a plenary session of the Key Committee in November 1929 to commence on a nationwide programme of collectivization.

Several forms of commonage farming were suggested by the People's Commissariat for Agriculture (Narkomzem), distinguished co-ordinate to the extent to which belongings was held in common:[12]

- Association for Joint Cultivation of State (Товарищество по совместной обработке земли, ТОЗ/TOZ), where only land was in mutual use;

- agronomical artel (initially in a loose significant, later formalized to go an organizational basis of kolkhozes, via The Standard Statute of an Agronomical Artel adopted by Sovnarkom in March 1930);

- agricultural commune, with the highest level of common utilize of resources.

Also, various cooperatives for the processing of agricultural products were installed.

In November 1929, the Central Commission decided to implement accelerated collectivization in the form of kolkhozes and sovkhozes. This marked the terminate of the New Economic Policy (NEP), which had allowed peasants to sell their surpluses on the open up market place. Peasants that were willing to conform and join the kolkhozes were rewarded with higher quality land and revenue enhancement breaks, whereas peasants were unwilling to bring together the kolkhozes were punished with being given lower quality land and increased taxes. The taxes imposed on the peasants was primarily to fund the industrial blitz that Stalin had made a priority.[10] If these lesser forms of social coercion proved to be ineffective and so the primal regime would resort to harsher forms of country coercion.[13] Stalin had many kulaks transported to collective farms in distant places to work in agricultural labour camps. In response to this, many peasants began to resist, often began arming themselves against the activists sent from the towns. As a form of protest, many peasants preferred to slaughter their animals for food rather than give them over to collective farms, which produced a major reduction in livestock.[14]

Collectivization had been encouraged since the revolution, but in 1928, but nigh one per cent of farmland was collectivized, and despite efforts to encourage and coerce collectivization, the rather optimistic first v-twelvemonth plan only forecast 15 per cent of farms to exist run collectively.[4]

All-out drive, winter 1929–xxx [edit]

The situation inverse rapidly in the autumn of 1929 and the winter of 1930. Between September and December 1929, collectivization increased from vii.four% to 15%, just in the commencement ii months of 1930, 11 million households joined collectivized farms, pushing the full to nearly sixty% nigh overnight.

To assist collectivization, the Party decided to send 25,000 "socially witting" manufacture workers to the countryside. This was accomplished from 1929–1933, and these workers have go known as twenty-five-thousanders ("dvadtsat'pyat'tysyachniki"). Soviet officials had hoped that by sending the 20-v thousanders to the countryside that they would exist able to produce grain more rapidly. Their hopes were that key areas in the Northward Caucasus and Volga regions would exist collectivized by 1931, then the other regions by 1932.[x] Shock brigades were used to strength reluctant peasants into joining the collective farms and remove those who were alleged kulaks and their "agents".

Collectivization sought to modernize Soviet agriculture, consolidating the land into parcels that could be farmed by modern equipment using the latest scientific methods of agronomics. It was often claimed that an American Fordson tractor (chosen "Фордзон" in Russian) was the all-time propaganda in favour of collectivization. The Communist Party, which adopted the plan in 1929, predicted an increment of 330% in industrial product, and an increase of 50% in agricultural production.

The means of production (land, equipment, livestock) were to exist totally "socialized", i.eastward. removed from the control of individual peasant households. Not even private household garden plots were immune.[ citation needed ]

Agricultural work was envisioned on a mass scale. Huge glamorous columns of machines were to piece of work the fields, in total contrast to peasant minor work.

The peasants traditionally mostly held their state in the form of large numbers of strips scattered throughout the fields of the hamlet community. Past an order of 7 Jan 1930, "all boundary lines separating the state allotments of the members of the artel are to be eliminated and all fields are to be combined in a single state mass." The bones rule governing the rearrangement of the fields was that the process would have to be completed earlier the spring planting.[15] The new kolkhozes were initially envisioned equally giant organizations unrelated to the preceding village communities. Kolkhozes of tens, or even hundreds, of thousands of hectares, were envisioned in schemes which were later to become known equally gigantomania. They were planned to exist "divided into 'economies (ekonomii)' of v,000–x,000 hectares which were in turn divided into fields and sections (uchastki) without regard to the existing villages – the aim was to achieve a 'fully depersonalized optimum state area'..."[ citation needed ] Parallel with this were plans to transfer the peasants to centralized 'agrotowns' offering modernistic amenities.

"Dizzy with Success" [edit]

The price of collectivization was so loftier that the March 2, 1930 event of Pravda contained Stalin'due south commodity Lightheaded with Success (Russian: Головокружение от успехов, lit.'Dizziness from success'),[16] in which he chosen for a temporary halt to the process:

It is a fact that by February 20 of this year 50 pct of the peasant farms throughout the U.S.S.R. had been collectivized. That means that by February 20, 1930, nosotros had overfulfilled the five-year program of collectivization by more than 100 per cent.... some of our comrades have get airheaded with success and for the moment accept lost clearness of heed and sobriety of vision.

After the publication of the commodity, the pressure for collectivization temporarily abated and peasants started leaving collective farms. Co-ordinate to Martin Kitchen, the number of members of commonage farms dropped by 50% in 1930. Only before long collectivization was intensified once again, and by 1936, about 90% of Soviet agriculture was collectivized.

Peasant resistance [edit]

YCLers seizing grain from "kulaks" which was hidden in the graveyard, Ukraine

Communist efforts to collectivize agronomics and eliminate independent property account account for the biggest expiry toll under Stalin'south dominion. Some peasants viewed collectivization as the stop of the world.[17] By no ways was joining the collective subcontract (also known as the kolkhoz) voluntary. The drive to collectivize understandably had little support from experienced farmers.[eighteen]

The intent was to withhold grain from the market and increment the total crop and food supply via state commonage farms.[19] The anticipated surplus would then pay for industrialization. The kulaks, (who were more often than not experienced farmers), were coerced into giving up their land to make way for these commonage farms or risk being killed, deported, or sent to labor camps. About one million kulak households (some five million people) were deported and never heard from over again. [20] Inexperienced peasants from urban areas would so replace the missing workforce of the agriculture sector, which is now considered overstaffed, inefficient and import-dependent.[21] Under Stalin'southward grossly inefficient organisation, agricultural yields declined rather than increased. The situation persisted into the 1980s, when Soviet farmers averaged about ten per centum of the output of their counterparts in the U.s.a.. [22] To make matters worst, tractors promised to the peasants could not exist produced due to the poor policies in the Industrial sector of the Soviet Union.[23]

Peasants tried to protest through peaceful ways past speaking out at collectivization meetings and writing letters to the central authorities with no avail. The kulaks argued to the collectors that starvation was inevitable, but they all the same started to seize everything edible from the kulaks to meet quotas, regardless if the kulaks had anything for themselves. Stalin falsely denied there even was a famine and prohibited journalists from visiting the collective farms. In order to cover upward for the poor harvests, the Soviet government created a trigger-happy propaganda campaign blaming the kulak for the dearth. The propaganda said they were creating an artificial food shortage past hiding crops merely to sell them when prices were high. The simulated propaganda also claimed kulaks were committing crimes such as arson, lynching, and murder of local government, kolkhoz, and activists. [24]

Historians agree that although there are records of kulaks hiding food, it'southward very clear they were out of survival. Despite the Soviet Matrimony destroying archives regarding this man-made dearth, (which in Ukraine is knows as "the Holodomor") it is recognized internationally as a genocide. [25]

Collectivization as a "2nd serfdom" [edit]

Rumors circulated in the villages warning the rural residents that collectivization would bring disorder, hunger, famine, and the devastation of crops and livestock.[26] Readings and reinterpretations of Soviet newspapers labelled collectivization as a second serfdom.[27] [28] Villagers were afraid the old landowners/serf owners were coming back and that the villagers joining the commonage subcontract would face starvation and famine.[29] More than reason for peasants to believe collectivization was a second serfdom was that entry into the kolkhoz had been forced. Farmers did not have the right to get out the collective without permission. The level of state procurements and prices on crops likewise enforced the serfdom analogy. The authorities would take a majority of the crops and pay extremely low prices. The serfs during the 1860s were paid nothing but collectivization still reminded the peasants of serfdom.[30] To them, this "second serfdom" became lawmaking for the Communist betrayal of the revolution. To the peasants, the revolution was about giving more freedom and country to the peasants, simply instead, they had to give up their country and livestock to the commonage subcontract which to some extent promoted communist policies.

Women's role in resistance [edit]

Women were the primary vehicle for rumours that touched upon issues of family and everyday life.[31] Fears that collectivization would result in the socialization of children, the export of women'due south hair, communal wife-sharing, and the notorious common coating affected many women, causing them to revolt[ citation needed ]. For example, when information technology was announced that a collective subcontract in Crimea would become a commune and that the children would be socialized[ citation needed ], women killed their presently-to-be socialized livestock, which spared the children[ citation needed ]. Stories that the Communists believed short pilus gave women a more urban and industrial look insulted peasant women.[32] After local activists in a village in North Caucasus actually confiscated all blankets, more than fearfulness dispersed among villagers. The mutual blanket meant that all men and women would sleep on a seven-hundred meter long bed under a seven-hundred-meter long blanket.[33] Historians contend that women took advantage of these rumours without actually believing them then they could set on the collective farm "under the guise of irrational, nonpolitical protestation."[34] Women were less vulnerable to retaliation than peasant men, and therefore able to get away with a lot more.[35]

Peasant women were rarely held accountable for their actions considering of the officials' perceptions of their protests. They "physically blocked the entrances to huts of peasants scheduled to be exiled equally kulaks, forcibly took back socialized seed and livestock and led assaults on officials." Officials ran abroad and hid to let the riots run their class. When women came to trial, they were given less harsh punishments as the men because women, to officials, were seen equally illiterate and the near backward part of the peasantry. One detail case of this was a riot in a Russian village of Belovka where protestors were beating members of the local soviet and setting fire to their homes. The men were held exclusively responsible as the chief culprits. Women were given sentences to serve as a warning, non as a penalisation. Because of how they were perceived, women were able to play an essential role in the resistance to collectivization.[36]

Religious persecution [edit]

Collectivization did not just entail the acquisition of land from farmers but also the endmost of churches, called-for of icons, and the arrests of priests. [29] Associating the church building with the tsarist regime,[37] the Soviet state continued to undermine the church building through expropriations and repression.[38] They cut off state financial support to the church and secularized church schools.[37] Peasants began to associate Communists with atheists because the attack on the church building was so devastating.[38] The Communist assault on religion and the church angered many peasants, giving them more reason to revolt. Riots exploded after the endmost of churches as early every bit 1929.[39]

Identification of Soviet power with the Antichrist also decreased peasant support for the Soviet regime. Rumors about religious persecution spread mostly by word of mouth, but as well through leaflets and proclamations.[40] Priests preached that the Antichrist had come to place "the Devil's mark" on the peasants.[41] and that the Soviet state was promising the peasants a better life just was really signing them up for Hell. Peasants feared that if they joined the commonage farm they would be marked with the stamp of the Antichrist.[42] They faced a choice between God and the Soviet collective subcontract. Choosing between salvation and damnation, peasants had no selection simply to resist the policies of the country.[43] These rumours of the Soviet state as the Antichrist functioned to keep peasants from succumbing to the government. The attacks on religion and the Church building affected women the nearly considering they were upholders of religion within the villages.[44]

Dovzhenko's pic Earth gives case of peasants' skepticism with collectivization on the basis that it was an assail on the church.[45] Coiner of the term genocide; Raphael Lemkin considered the repression of the Orthodox Church to exist a prong of genocide against Ukrainians when seen in correlation to the Holodomor famine.[46]

Results [edit]

Resistance to collectivization and consequences [edit]

American press with information about dearth

Pavlik Morozov (second row, in the middle): this is the merely surviving photo known of him.

Due to the high government product quotas, peasants received, as a dominion, less for their labour than they did before collectivization, and some refused to piece of work. Merle Fainsod estimated that, in 1952, commonage farm earnings were only i-4th of the cash income from individual plots on Soviet commonage farms.[47] In many cases, the immediate effect of collectivization was the reduction of output and the cutting of the number of livestock in half. The subsequent recovery of the agricultural production was also impeded past the losses suffered past the Soviet Spousal relationship during Earth State of war II and the severe drought of 1946. However, the largest loss of livestock was caused by collectivization for all animals except pigs.[48] The numbers of cows in the USSR fell from 33.ii million in 1928 to 27.8 million in 1941 and to 24.6 million in 1950. The number of pigs cruel from 27.seven million in 1928 to 27.5 million in 1941 and then to 22.2 million in 1950. The number of sheep brutal from 114.six million in 1928 to 91.six 1000000 in 1941 and to 93.half-dozen million in 1950. The number of horses fell from 36.ane million in 1928 to 21.0 one thousand thousand in 1941 and to 12.7 million in 1950. Only by the tardily 1950s did Soviet farm animal stocks brainstorm to approach 1928 levels.[48]

Despite the initial plans, collectivization, accompanied by the bad harvest of 1932–1933, did non live up to expectations. Between 1929 and 1932 there was a massive fall in agricultural output resulting in dearth in the countryside. Stalin and the CPSU blamed the prosperous peasants, referred to every bit 'kulaks' (Russian: fist), who were organizing resistance to collectivization. Allegedly, many kulaks had been hoarding grain in order to speculate on higher prices, thereby sabotaging grain drove. Stalin resolved to eliminate them every bit a class. The methods Stalin used to eliminate the kulaks were dispossession, deportation, and execution. The term "Ural-Siberian Method" was coined past Stalin, the rest of the population referred to it equally the "new method". Commodity 107 of the criminal lawmaking was the legal ways by which the state caused grain.[23]

The Soviet government responded to these acts past cutting off food rations to peasants and areas where at that place was opposition to collectivization, particularly in Ukraine. For peasants that were unable to see the grain quota, they were fined five-times the quota. If the peasant continued to exist defiant the peasants' holding and equipment would be confiscated past the state. If none of the previous measures were effective the defiant peasant would be deported or exiled. The practice was made legal in 1929 under Commodity 61 of the criminal code.[23] Many peasant families were forcibly resettled in Siberia and Kazakhstan into exile settlements, and most of them died on the mode. Estimates suggest that about a million so-called 'kulak' families, or perhaps some five 1000000 people, were sent to forced labour camps.[49] [l]

On August seven, 1932, the Decree about the Protection of Socialist Holding proclaimed that the punishment for theft of kolkhoz or cooperative property was the decease sentence, which "under extenuating circumstances" could be replaced by at least x years of incarceration. With what some chosen the Law of Spikelets ("Закон о колосках"), peasants (including children) who paw-collected or gleaned grain in the collective fields after the harvest were arrested for damaging the country grain production. Martin Amis writes in Koba the Dread that 125,000 sentences were passed for this particular offence in the bad harvest period from August 1932 to December 1933.

During the Famine of 1932–33 it'southward estimated that vii.8–11 million people died from starvation.[51] The implication is that the full death cost (both direct and indirect) for Stalin's collectivization program was on the order of 12 million people.[50] Information technology is said that in 1945, Joseph Stalin confided to Winston Churchill at Yalta that 10 one thousand thousand people died in the form of collectivization.[52]

Siberia [edit]

Since the second one-half of the 19th century, Siberia had been a major agricultural region within Russia, espеcially its southern territories (nowadays Altai Krai, Omsk Oblast, Novosibirsk Oblast, Kemerovo Oblast, Khakassia, Irkutsk Oblast). Stolypin'due south plan of resettlement granted a lot of country for immigrants from elsewhere in the empire, creating a large portion of well-off peasants and stimulating rapid agricultural development in the 1910s. Local merchants exported large quantities of labelled grain, flour, and butter into fundamental Russian federation and Western Europe.[53] In May 1931, a special resolution of the Western-Siberian Regional Executive Committee (classified "acme secret") ordered the expropriation of belongings and the deportation of 40,000 kulaks to "sparsely populated and unpopulated" areas in Tomsk Oblast in the northern part of the Western-Siberian region.[54] The expropriated property was to be transferred to kolkhozes as indivisible collective property and the kolkhoz shares representing this forced contribution of the deportees to kolkhoz equity were to be held in the "collectivization fund of poor and landless peasants" (фонд коллективизации бедноты и батрачества).

It has since been perceived past historians such as Lynne Viola as a Civil War of the peasants confronting the Bolshevik Government and the attempted colonization of the countryside.[55]

Central Asia and Kazakhstan [edit]

In 1928 within Soviet Kazakhstan, authorities started a campaign to confiscate cattle from richer Kazakhs, who were called bai, known as Little October. The confiscation campaign was carried out past Kazakhs against other Kazakhs, and it was up to those Kazakhs to make up one's mind who was a bai and how much to confiscate from them.[56] This engagement was intended to brand Kazakhs agile participants in the transformation of Kazakh social club.[57] More than 10,000 bais may accept been deported due to the campaign against them.[58] In areas where the major agronomical activity was nomadic herding, collectivization met with massive resistance and major losses and confiscation of livestock. Livestock in Kazakhstan fell from 7 1000000 cattle to i.half-dozen one thousand thousand and from 22 million sheep to 1.vii meg. Restrictions on migration proved ineffective and one-half a million migrated to other regions of Cardinal Asia and 1.5 million to China.[59] Of those who remained, as many as a meg died in the resulting famine.[sixty] In Mongolia, a and then-called 'Soviet dependency', attempted collectivization was abandoned in 1932 after the loss of 8 million caput of livestock.[61]

Historian Sarah Cameron argues that while Stalin did non intend to starve Kazakhs, he saw some deaths every bit a necessary sacrifice to accomplish the political and economic goals of the regime.[62] Cameron believes that while the famine combined with a campaign confronting nomads was non genocide in the sense of the United Nations (UN) definition, information technology complies with Raphael Lemkin'southward original concept of genocide, which considered destruction of culture to be every bit genocidal as concrete annihilation.[63] Historian Stephen Wheatcroft criticizes this view in regard to the Soviet famine because he believes that the high expectations of central planners was sufficient to demonstrate their ignorance of the ultimate consequences of their actions and that the result of them would be famine.[63] Niccolò Pianciola goes further than Cameron and argues that from Lemkin'southward point of view on genocide all nomads of the Soviet Wedlock were victims of the crime, not just the Kazakhs.[64]

Ukraine [edit]

Near historians hold that the disruption caused by collectivization and the resistance of the peasants significantly contributed to the Great Famine of 1932–1933, especially in Ukraine, a region famous for its rich soil (chernozem). This particular period is chosen "Holodomor" in Ukrainian. During the like famines of 1921–1923, numerous campaigns – inside the state, as well equally internationally – were held to enhance money and food in support of the population of the afflicted regions. Nothing similar was done during the drought of 1932–1933, mainly considering the information about the disaster was suppressed by Stalin.[65] [66] Stalin also undertook a purge of the Ukrainian communists and intelligentsia, with devastating long-term effects on the expanse.[67] Many Ukrainian villages were blacklisted and penalized by government prescript for perceived demolition of food supplies.[68] Moreover, migration of population from the affected areas was restricted.[69] [70] According to Stalin in his conversation with the prize-winning author Mikhail Sholokhov, the famine was acquired past the excesses of local party workers and sabotage,

I've thanked you for the letters, as they betrayal a sore in our Party-Soviet work and show how our workers, wishing to curb the enemy, sometimes unwittingly hit friends and descend to sadism. ... the esteemed grain-growers of your district (and not only of your district lonely) carried on an 'Italian strike' (sabotage!) and were not loath to go out the workers and the Red Army without bread. That the sabotage was quiet and outwardly harmless (without claret) does not modify the fact that the esteemed grain-growers waged what was in fact a 'quiet' war confronting Soviet power. A war of starvation, dear com[rade] Sholokhov. This, of course, can in no way justify the outrages, which, as you lot assure me, have been committed past our workers. ... And those guilty of those outrages must be duly punished.[71] [72]

Starved peasants on a street in Kharkiv, 1933

About forty meg people were affected by the food shortages including areas near Moscow where bloodshed rates increased past l%.[73] The middle of the famine, however, was Ukraine and surrounding regions, including the Don, the Kuban, the Northern Caucasus and Republic of kazakhstan where the price was one 1000000 dead. The countryside was affected more than cities, but 120,000 died in Kharkiv, 40,000 in Krasnodar and xx,000 in Stavropol.[73]

The declassified Soviet archives evidence that there were ane.54 1000000 officially registered deaths in Ukraine from famine.[74] Alec Nove claims that registration of deaths largely ceased in many areas during the famine.[75] However, information technology's been pointed out that the registered deaths in the archives were essentially revised past the demographics officials. The older version of the information showed 600,000 fewer deaths in Ukraine than the current, revised statistics.[74] In The Black Book of Communism, the authors claim that the number of deaths was at to the lowest degree 4 million, and they also characterize the Smashing Dearth as "a genocide of the Ukrainian people".[76] [77]

Latvia [edit]

Later the Soviet Occupation of Republic of latvia in June 1940, the state's new rulers were faced with a problem: the agricultural reforms of the inter-war period had expanded private holdings. The belongings of "enemies of the people" and refugees, equally well as those above 30 hectares, was nationalized in 1940–44, but those who were nevertheless landless were then given plots of 15 hectares each. Thus, Latvian agriculture remained essentially dependent on personal smallholdings, making central planning difficult. In 1940–41 the Communist Party repeatedly said that collectivization would not occur forcibly, just rather voluntarily and by example. To encourage collectivization high taxes were enforced and new farms were given no government support. But subsequently 1945 the Party dropped its restrained arroyo as the voluntary approach was not yielding results. Latvians were accepted to individual holdings (viensētas), which had existed even during serfdom, and for many farmers, the plots awarded to them by the interwar reforms were the first their families had ever endemic. Furthermore, the countryside was filled with rumours regarding the harshness of commonage subcontract life.

Pressure from Moscow to collectivize continued and the authorities in Latvia sought to reduce the number of private farmers (increasingly labelled kulaki or budži) through higher taxes and requisitioning of agricultural products for state apply. The get-go kolkhoz was established merely in November 1946 and by 1948, merely 617 kolkhozes had been established, integrating xiii,814 individual farmsteads (12.half dozen% of the total). The process was still judged likewise tiresome, and in March 1949 just under 13,000 kulak families, also equally a big number of individuals, were identified. Between March 24 and March xxx, 1949, about forty,000 people were deported and resettled at various points throughout the USSR.

Later on these deportations, the pace of collectivization increased as a inundation of farmers rushed into kolkhozes. Inside 2 weeks 1740 new kolkhozes were established and by the terminate of 1950, just 4.5% of Latvian farmsteads remained outside the collectivized units; nearly 226,900 farmsteads belonged to collectives, of which there were at present around xiv,700. Rural life changed as farmers' daily movements were dictated to past plans, decisions, and quotas formulated elsewhere and delivered through an intermediate non-farming hierarchy. The new kolkhozes, especially smaller ones, were ill-equipped and poor – at first farmers were paid once a year in kind so in cash, but salaries were very small and at times farmers went unpaid or fifty-fifty ended up owing coin to the kholhoz. Farmers all the same had small-scale pieces of land (non larger than 0.5 ha) around their houses where they grew food for themselves. Along with collectivization, the regime tried to uproot the custom of living in individual farmsteads by resettling people in villages. However this process failed due to lack of money since the Soviets planned to move houses as well.[78] [79]

Progress of collectivization, 1927–1940 [edit]

| Twelvemonth | Number of collective farms | Percent of farmsteads in collective farms | Percent of sown area in collective use |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1927 | xiv,800 | 0.eight | – |

| 1928 | 33,300 | 1.7 | 2.3 |

| 1929 | 57,000 | 3.9 | 4.nine |

| 1930 | 85,900 | 23.6 | 33.6 |

| 1931 | 211,100 | 52.7 | 67.8 |

| 1932 | 211,100 | 61.five | 77.7 |

| 1933 | 224,500 | 65.vi | 83.1 |

| 1934 | 233,300 | 71.4 | 87.4 |

| 1935 | 249,400 | 83.2 | 94.1 |

| 1936 | – | xc.5 | 98.ii |

| 1937 | 243,700 | 93.0 | 99.one |

| 1938 | 242,400 | 93.5 | 99.8 |

| 1939 | 235,300 | 95.6 | – |

| 1940 | 236,900 | 96.9 | 99.8 |

Sources: Sotsialisticheskoe sel'skoe khoziaistvo SSSR, Gosplanizdat, Moscow-Leningrad, 1939 (pp. 42, 43); supplementary numbers for 1927–1935 from Sel'skoe khoziaistvo SSSR 1935, Narkomzem SSSR, Moscow, 1936 (pp. 630, 634, 1347, 1369); 1937 from Bang-up Soviet Encyclopedia, vol. 22, Moscow, 1953 (p. 81); 1939 from Narodnoe khoziaistvo SSSR 1917–1987, Moscow, 1987 (pp. 35); 1940 from Narodnoe khoziaistvo SSSR 1922–1972, Moscow, 1972 (pp. 215, 240).

The official numbers for the collectivized areas (the column with per cent of sown area in collective use in the tabular array above) are biased up past two technical factors. First, these official numbers are calculated as a per cent of sown area in peasant farmsteads, excluding the area cultivated by sovkhozes and other agricultural users. Estimates based on the total sown expanse (including state farms) reduce the share of commonage farms between 1935–1940 to about eighty%. Second, the household plots of kolkhoz members (i.e., collectivized farmsteads) are included in the state base of operations of commonage farms. Without the household plots, arable land in collective cultivation in 1940 was 96.4% of land in commonage farms, and not 99.8% every bit shown past official statistics. Although there is no arguing with the fact that collectivization was sweeping and full betwixt 1928 and 1940, the tabular array below provides different (more realistic) numbers on the extent of collectivization of sown areas.

Distribution of sown area by land users, 1928 and 1940

| Land users | 1928 | 1940 |

|---|---|---|

| All farms, '000 hectares | 113,000 | 150,600 |

| Country farms (sovkhozes) | ane.5% | 8.8% |

| Collective farms (kolkhozes) | 1.2% | 78.2% |

| Household plots (in commonage and land farms) | ane.1% | 3.5% |

| Peasant farms and other users | 96.2% | 9.5% |

Source: Narodnoe khoziaistvo SSSR 1922–1972, Moscow, 1972 (p. 240).

Decollectivization under German occupation [edit]

During World State of war II, Alfred Rosenberg, in his capacity as the Reich Government minister for the Occupied Eastern Territories, issued a serial of posters announcing the end of the Soviet collective farms in areas of the USSR under German occupation. He also issued an Agrarian Police in February 1942, annulling all Soviet legislation on farming, restoring family unit farms for those willing to collaborate with the occupiers. But decollectivization conflicted with the wider demands of wartime food product, and Hermann Göring demanded that the kolkhoz be retained, save for a change of name. Hitler himself denounced the redistribution of land as 'stupid.'[80] [81] In the end, the German language occupation authorities retained well-nigh of the kolkhozes and just renamed them "community farms" (Russian: Общинные хозяйства, a throwback to the traditional Russian commune). German propaganda described this as a preparatory stride toward the ultimate dissolution of the kolkhozes into private farms, which would be granted to peasants who had loyally delivered compulsory quotas of farm produce to the Germans. Past 1943, the German occupation regime had converted thirty% of the kolkhozes into High german-sponsored "agronomical cooperatives", simply as still had made no conversions to individual farms.[82] [83]

See also [edit]

- Bibliography of Stalinism and the Soviet Union § Agronomics and the peasantry

- Collectivization in Hungary

- Collectivization in Poland

- Collectivization in Romania

- Collectivization in Yugoslavia

- Prescript on Land

- Dekulakization

- History of the Soviet Union (1927–53)

- Holodomor

- Order for Settling Toiling Jews on the State

- Soviet dearth of 1932–33

- Stalin's Peasants: Resistance and Survival in the Russian Hamlet afterward Collectivization (book)

Footnotes [edit]

- ^ McCauley, Martin, Stalin and Stalinism, p. 25, Longman Group, England, ISBN 0-582-27658-half-dozen

- ^ Davies, R.Due west., The Soviet Collective Farms, 1929–1930, Macmillan, London (1980), p. 1.

- ^ Himka, John-Paul (Spring 2013). "Encumbered Retentiveness: The Ukrainian Famine of 1932–33". Kritika: Explorations in Russian and Eurasian History. fourteen (ii): 411–36. doi:10.1353/kri.2013.0025. S2CID 159967790.

- ^ a b c d eastward A History of the Soviet Union from Beginning to Stop. Kenez, Peter. Cambridge Academy Press, 1999.

- ^ Conquest, Robert (2001). Reflections on a Ravaged Century. W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN978-0-393-32086-2.

- ^ p. 87, Harvest of Sorrow ISBN 0-19-504054-six, Conquest cites Lewin pp. 36–37, 176

- ^ Fainsod, Merle (1970). How Russia is Ruled (revised ed.). Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Printing. p. 526. ISBN9780674410008.

- ^ Fainsod (1970), p. 529.

- ^ a b Iordachi, Constantin; Bauerkämper, Arnd (2014). Collectivization of Agriculture in Communist Eastern Europe: Comparing and Entanglements. Budapest, New York: Central European Academy Press. ISBN978-6155225635. JSTOR ten.7829/j.ctt6wpkqw. ProQuest 1651917124.

- ^ a b c McCauley 2008[ page needed ]

- ^ Grigor., Suny, Ronald (1998). The Soviet experiment Russia, the USSR, and the successor states . Oxford Academy Printing. ISBN978-0195081046. OCLC 434419149.

- ^ James W. Heinzen, "Inventing a Soviet Countryside: State Power and the Transformation of Rural Russia, 1917–1929", University of Pittsburgh Press (2004) ISBN 0-8229-4215-1, Chapter one, "A Fake Start: The Birth and Early Activities of the People's Commissariat of Agriculture, 1917–1920"

- ^ Livi-Bassi, Massimo (1993). "On the Human Price of Collectivization in the Soviet Wedlock". Population and Development Review. Population and Evolution Review (19): 743–766. doi:ten.2307/2938412. JSTOR 2938412.

- ^ "Collectivization". Seventeen Moments in Soviet History. June 17, 2015. Retrieved February iii, 2019.

- ^ James R Millar, ed., The Soviet Rural Customs (Academy of Illinois Press, 1971), pp. 27–28.

- ^ "Giddy with Success". world wide web.marxists.org . Retrieved December 14, 2021.

- ^ Lynne Viola, Peasant Rebels Under Stalin: Collectivization and the Civilisation of Peasant Resistance (Oxford Academy Printing, 1996), 3–12.

- ^ Fitzpatrick, Sheila (1994). Stalin's Peasants: Resistance and Survival in the Russian Village After Collectivization . Oxford Academy Press. pp. 3–eighteen. ISBN978-0-19-506982-2.

- ^ Fitzpatrick (1994), p. 4.

- ^ "Stalin 1928-1933 - Collectivization". www.globalsecurity.org . Retrieved May 9, 2022.

- ^ Petrick, Martin (December i, 2021). "Postal service-Soviet Agricultural Restructuring: A Success Story Subsequently All?". Comparative Economic Studies. 63 (4): 623–647. doi:10.1057/s41294-021-00172-i. ISSN 1478-3320.

- ^ Hays, Jeffrey. "Agriculture IN THE SOVIET ERA | Facts and Details". factsanddetails.com . Retrieved May ix, 2022.

- ^ a b c Hughes, James (Spring 1994). "Capturing the Russian Peasantry: Stalinist Grain Procurement Policy and the Ural-Siberian Method". Slavic Review. 53 (1): 76–103. doi:10.2307/2500326. JSTOR 2500326.

- ^ "Common Lies nigh the Holodomor • Ukraїner". Ukraїner. November one, 2020. Retrieved May 9, 2022.

- ^ "Validate User". academic.oup.com . Retrieved May 9, 2022.

- ^ Viola, Peasant Rebels Under Stalin, threescore.

- ^ Fitzpatrick (1994), p. 67.

- ^ Viola, Peasant Rebels Under Stalin, 3.

- ^ a b Fitzpatrick (1994), p. 6.

- ^ Fitzpatrick (1994), p. 129.

- ^ Viola, "The Peasant Nightmare," 760.

- ^ Lynne Viola, "Bab'i bunti and peasant women's protest during collectivization," in The Stalinist Dictatorship, ed. Chris Ward. (London; New York: Arnold, 1998), 218–19.

- ^ Viola, "The Peasant Nightmare," 765.

- ^ Viola, "Bab'i bunti," 218–19.

- ^ Viola, "Bab'i bunti," 224–25.

- ^ Viola, "Bab'i bunti," 220–22.

- ^ a b Fitzpatrick (1994), p. 33.

- ^ a b Viola, Peasant Rebels Under Stalin, 49.

- ^ Viola, Peasant Rebels under Stalin, 157.

- ^ Viola, "The Peasant nightmare," 762.

- ^ Fitzpatrick (1994), p. 45.

- ^ Viola, Peasant Rebels Under Stalin, 63.

- ^ Viola, "The Peasant nightmare," 767.

- ^ Viola, "Bab'i bunti", 217–18.

- ^ Dovzhenko, Aleksandr (October 17, 1930), Globe, Stepan Shkurat, Semyon Svashenko, Yuliya Solntseva, retrieved March 25, 2018

- ^ Serbyn, Roman. "Function of Lemkin". HREC Education. Archived from the original on May thirty, 2019. Retrieved January xx, 2021.

- ^ Fainsod (1970), p. 542.

- ^ a b Fainsod (1970), p. 541.

- ^ Fainsod (1970), p. 526.

- ^ a b Hubbard, Leonard Eastward. (1939). The Economic science of Soviet Agriculture. Macmillan and Co. pp. 117–18.

- ^ McCauley, Martin (2013). Stalin and Stalinism. Routledge. p. 43.

- ^ Joseph Stalin: A Biographical Companion by Helen Rappaport, p. 53

- ^ "Commerce in the Siberian town of Berdsk, early 20th century". Archived from the original on December 24, 2004.

- ^ Western-Siberian resolution of deportation of 40,000 kulaks to northern Siberia, May 5, 1931.

- ^ Viola, Lynne, Peasant Rebels Under Stalin: Collectivization and the Culture of Peasant Resistance, Oxford Academy Printing, Oxford (1996), p. 3.

- ^ Cameron, Sarah (2018). The Hungry Steppe: Dearth, Violence, and the Making of Soviet Kazakhstan. Cornell University Press. p. 71. ISBN9781501730443.

- ^ Cameron, Sarah (2018). The Hungry Steppe: Famine, Violence, and the Making of Soviet Kazakhstan. Cornell University Press. p. 72. ISBN9781501730443.

- ^ Cameron, Sarah (2018). The Hungry Steppe: Dearth, Violence, and the Making of Soviet Republic of kazakhstan. Cornell Academy Press. p. 95. ISBN9781501730443.

- ^ Courtois, Stéphane, ed. (1999). The Blackness Book of Communism: Crimes, Terror, Repression. Harvard University Press. p. 168. ISBN978-0-674-07608-2.

- ^ Pannier, Bruce (Dec 28, 2007). "Kazakhstan: The Forgotten Famine". Radio Complimentary Europe / Radio Freedom.

- ^ Conquest, Robert (October 9, 1986). "Key Asia and the Kazakh Tragedy". Harvest of Sorrow: Soviet Collectivization and the Terror-Dearth. Oxford University Printing. pp. 189–198. ISBN978-0-19-504054-8.

- ^ Cameron, Sarah (2018). The Hungry Steppe: Famine, Violence, and the Making of Soviet Kazakhstan. Cornell University Press. p. 99. ISBN9781501730443.

- ^ a b Wheatcroft, Stephen Chiliad. (August 2020). "The Complexity of the Kazakh Famine: Food Problems and Faulty Perceptions". Journal of Genocide Research. 23 (iv): 593–597. doi:10.1080/14623528.2020.1807143. S2CID 225333205.

- ^ Pianciola, Niccolò (Baronial 2020). "Environment, Empire, and the Great Famine in Stalin's Republic of kazakhstan". Journal of Genocide Research. 23 (4): 588–592. doi:10.1080/14623528.2020.1807140. S2CID 225294912.

- ^ Courtois, S. (1997). The Blackness Book of Communism. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. p. 159.

- ^ Courtois (1997), p. 159.

- ^ "Ukrainian Famine". Excerpts from the Original Electronic Text at the spider web site of Revelations from the Russian Archives (Library of Congress). Hanover College.

- ^ "Grain Problem". Addendum to the minutes of Politburo [meeting] No. 93. Library of Congress. Dec six, 1932.

- ^ Courtois (1997), p. 164.

- ^ "Revelations from the Russian Athenaeum: Ukrainian Dearth". Library of Congress.

- ^ "Correspondence between Joseph Stalin and Mikhail Sholokhov published in Вопросы истории, 1994, № 3, с. nine–24". Archived from the original on August 16, 2018. Retrieved November 26, 2016.

- ^ Courtois, Stéphane, Werth Nicolas , Panné Jean-Louis , Paczkowski Andrzej , Bartošek Karel , Margolin Jean-Louis Czarna księga komunizmu. Zbrodnie, terror, prześladowania. Prószyński i S-ka, Warszawa 1999. 164–165

- ^ a b Courtois (1997), p. 167.

- ^ a b Wheatcroft, Stephen; Davies, RW (2004). The Years of Hunger: Soviet Agriculture, 1931–1933. Palgrave MacMillan.

- ^ Nove, Alec (1993). "Victims of Stalinism: How Many?". In Getty, J. Arch; Manning, Roberta T. (eds.). Stalinist Terror: New Perspectives . Cambridge University Press. pp. 266. ISBN978-0-521-44670-9.

- ^ Courtois (1997), p. 168.

- ^ Merl, S. (1995). "Golod 1932–1933: Genotsid Ukraintsev dlya osushchestvleniya politiki russifikatsii? (The famine of 1932–1933: Genocide of the Ukrainians for the realization of the policy of Russification?)". Otechestvennaya istoriya. Vol. 1. pp. 49–61.

- ^ Plakans, Andrejs (1995). The Latvians: A Short History . Stanford: Hoover Institution Press. pp. 155–56.

- ^ Freibergs, J. (2001) [1998]. Jaunako laiku vesture 20. gadsimts. Zvaigzne ABC. ISBN978-9984-17-049-7.

- ^ Leonid Grenkevich, The Soviet Partisan Motility, 1941–1945: A Critical Historiographical Assay, Routledge, New York (1999), pp. 169–71.

- ^ Memorandum by Brautigam apropos conditions in occupied areas of the USSR, 25 October 1942. Archived 24 February 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Joseph Fifty. Wieczynski, ed., The Mod Encyclopedia of Russian and Soviet History, Academic International Printing, Gulf Breeze, FL, 1978, vol. vii, pp. 161–62.

- ^ Alexander Dallin, German Dominion in Russian federation, 1941–1945: A Written report of Occupation Politics (London, Macmillan, 1957), pp. 346–51; Karl Brandt, Otto Schiller, and Frantz Anlgrimm, Management of Agronomics and Food in the German-Occupied and Other Areas of Fortress Europe (Stanford, California, Stanford University Printing, 1953), pp. 92ff. [pp. 96–99, gives an interesting case written report of the dissolution process]

Further reading [edit]

- Ammende, Ewald. "Human life in Russia", (Cleveland: J.T. Zubal, 1984), Reprint, Originally published: London, England: Allen & Unwin, 1936, ISBN 0-939738-54-6

- Conquest, Robert. The Harvest of Sorrow: Soviet Collectivization and the Terror-Famine, Oxford Academy Press, 1986.

- Davies, R. Due west. The Socialist Offensive (Volume one of The Industrialization of Soviet Russia), Harvard University Press (1980), hardcover, ISBN 0-674-81480-0

- Davies, R. W. The Soviet Collective Farm, 1929–1930 (Volume 2 of the Industrialization of Soviet Russia), Harvard Academy Printing (1980), hardcover, ISBN 0-674-82600-0

- Davies, R. W., Soviet Economy in Turmoil, 1929–1930 (book 3 of The Industrialization of Soviet Russia), Harvard University Press (1989), ISBN 0-674-82655-8

- Davies, R.West. and Stephen G. Wheatcroft. Years of Hunger: Soviet Agriculture, 1931–1933, (book 4 of The Industrialization of Soviet Russian federation), Palgrave Macmillan (Apr, 2004), hardcover, ISBN 0-333-31107-8

- Davies, R. W. and S. G. Wheatcroft. Materials for a Balance of the Soviet National Economy, 1928–1930, Cambridge Academy Press (1985), hardcover, 467 pages, ISBN 0-521-26125-2

- Dolot, Miron. Execution by Hunger: The Hidden Holocaust, Westward. W. Norton (1987), trade paperback, 231 pages, ISBN 0-393-30416-7; hardcover (1985), ISBN 0-393-01886-5

- Kokaisl, Petr. Soviet Collectivisation and Its Specific Focus on Central Asia Agris Volume V, Number 4, 2013, pp. 121–133, ISSN 1804-1930.

- Hindus, Maurice. Red Bread: Collectivization in a Russian Village [1931]. Bllomingtonm, IN: Indiana Academy Printing, 1988.[ ISBN missing ]

- Laird, Roy D. "Collective Farming in Russia: A Political Study of the Soviet Kolkhozy", Academy of Kansas, Lawrence, KS (1958), 176 pp.[ ISBN missing ]

- Lewin, Moshe. Russian Peasants and Soviet Ability: A Study of Collectivization, W.Due west. Norton (1975), trade paperback, ISBN 0-393-00752-nine

- Library of Congress Revelations from the Russian Archives: Collectivization and Industrialization (master documents from the flow)

- Martens, Ludo. United nations autre regard sur Staline, Éditions EPO, 1994, 347 pages, ISBN ii-87262-081-8. See the section "External links" for an English translation.

- McCauley, Martin (2008). Stalin and Stalinism (Revised, third ed.). Harlow, England: Pearson Longman. ISBN978-1405874366. OCLC 191898287.

- Nimitz, Nancy. "Farm Development 1928–62", in Soviet and East European Agricultures, Jerry F. Karcz, ed. Berkeley, California: University of California, 1967.[ ISBN missing ]

- Satter, David. Historic period of Delirium : The Turn down and Fall of the Soviet Marriage, Yale University Press, 1996.[ ISBN missing ]

- Taylor, Sally J. Stalin's Apologist: Walter Duranty : The New York Times's Man in Moscow, Oxford Academy Printing (1990), hardcover, ISBN 0-19-505700-7

- Tottle, Douglas. Fraud, Dearth and Fascism: The Ukrainian genocide myth from Hitler to Harvard. Toronto: Progress Books, 1987[ ISBN missing ]

- Wesson, Robert G. "Soviet Communes." Rutgers Academy Printing, 1963[ ISBN missing ]

- Zaslavskaya, Tatyana. The Second Socialist Revolution, ISBN 0-253-20614-6

External links [edit]

-

Media related to Collectivization in the Soviet Wedlock at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Collectivization in the Soviet Wedlock at Wikimedia Commons - "The Collectivization 'Genocide'", in Another View of Stalin, by Ludo Martens. Translated from the French book United nations autre regard sur Staline, listed above under "References and further reading".

- "Reply to Commonage Farm Comrades" by Stalin

- Ukrainian Famine: Excerpts from the Original Electronic Text at the spider web site of Revelations from the Russian Archives

- "Soviet Agriculture: A critique of the myths constructed by Western critics", by Joseph Eastward. Medley, Department of Economics, University of Southern Maine (Us).

- "The Ninth Circumvolve", past Olexa Woropay

- Prize-winning essay on FamineGenocide.com

- 1932–34 Bully Famine: documented view by Dr. Dana Dalrymple

- COLLECTIVIZATION AND INDUSTRIALIZATION Revelations from the Russian Archives at the Library of Congress

- Russia's Necropolis of Terror and the Gulag. This select directory of burial grounds and commemorative sites includes 138 abased deportees graveyards left behind past dekulakized peasants and later forced settlers.

Who Owned And Controlled The Soviet Union's Collective Farms,

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Collectivization_in_the_Soviet_Union

Posted by: lorenzothaveres.blogspot.com

0 Response to "Who Owned And Controlled The Soviet Union's Collective Farms"

Post a Comment